Let’s face it, the short story is a fading art form that most modern readers ignore. The short story will never fade away completely because of would-be novelists, MFA Creative Writing students, and legions of fan fiction writers. The short story existed before mid-19th century in proto-forms, had it’s heyday of mass popularity from the 1850s to the 1950s, and continues to exist now in various subcultures centered around mystery and science fiction writers, academic literary writers, and fanfic writers. Before television in the 1950s, there were hundreds of magazines devoted to the short story, filling the newsstands each week, that were read by the masses as a popular entertainment. Television killed that publishing industry. Today if you search hard at good bookstores, you can find a handful of story magazines to buy. Most literary magazines have print runs in the hundreds, or low thousands, and a handful of genre magazines have paid circulations in 20,000-30,000 range.

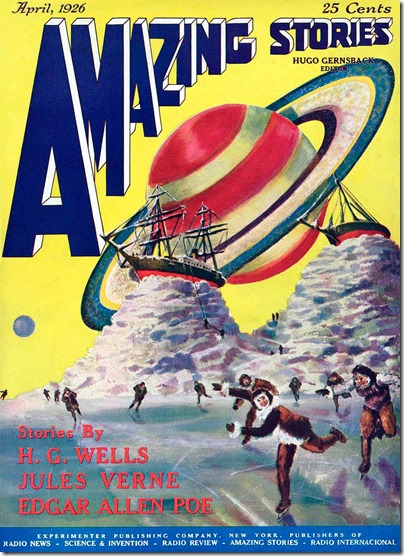

My motive for writing this essay is to give modern science fiction fans a sense of history of how science fictional ideas emerged out of magazines in the 19th century, grew in popularity with the general fiction pulp magazines of the early part of the 20th century, coalesced into a specific genre pulps starting in 1926 with Amazing Stories, grew even more in popularity in the 1930s and 1940s in many more pulp titles in the U.S. and Great Britain, and peaked in the 1950s and 1960s, when the SF novel became the dominant form of expressing science fictional ideas, and afterwards when television and movies became the main purveyor of science fiction.

In the 19th century the genres we know today were all available in general circulation magazines. The rise of the literate middle class, combined with the advent of cheap publishing, created a reading boom. Think of 19th century magazines as the television of its day – the technology of how people studied the world then, because they didn’t have the radio, television, or the Internet.

All subjects and genres have probably existed for millennia as oral tales, myths, bible stories, anecdotes and even jokes, but as they gelled in the 19th century, certain favorite fictional topics and genres emerged, and maybe the last and least of them, was science fiction.

- Sex – stories of romance, courtship, sex, marriage, children, families have always been the most popular story subject.

- Mystery – murder, crime, detectives right from the beginning, especially with Edgar Allan Poe, have been the next big favorite.

- History – recreating the past has always had its reading fans.

- Westerns – came out of the urge to write historical fiction to become it’s own genre.

- Fantasy – the supernatural and magic is probably the first genre. Horror is a major sub-genre. Think ghost stories.

- Intrigue – Tightly plotted stories of conflict over politics, espionage, money, industry, diplomacy has a distinctive readership.

- Travel – people in the 19th century couldn’t get enough reporting from other lands, and even in the 21st century with television and the internet, fiction about travel is still popular.

- Humor – ranges from crude to highbrow, and is very hard to write.

- War – many people consider history the chronicles of wars, but war fiction is about humans at their worst and best.

- Sports – games, hunting, fishing, living in the great outdoors

- Forbidden – Pornography, sadism, masochism, perversion – all the stuff kept under the counter.

- Future – it’s very hard to define science fiction, but generally it’s stories about the future. In the 19th century it was often about planned utopias, speculation about disturbing trends, how inventions would change society, the marvels of possible new discoveries, and that emerging academic discipline, science.

No categorization is perfect, and most stories involve cross fertilization. Starting with a microscopic audience in the distant past, to a massive audience today, stories about science fictional ideas have appealed to a segment of readers. For most of literary history there has been little demarcation between fantasy and science fiction. Mostly, this was due to the concept of science and scientists having not been invented. It wasn’t until the 1830s that science as a discipline and label was created, so it’s not surprising that it was until the 1930s that the term “science fiction” finally caught on, and even until the 1950s that it was widely use. Nowadays, in the 21st century, most people associate the term with movies and television shows, and not books, and definitely not short stories. But I firmly believe it’s the short story where the best SF ideas emerge first.

We know speculation about intelligent life on other worlds has existed as far back as classical Greek times, and that stories about space travel, artificial life, mechanical beings, and such have appeared occasionally throughout the centuries, but there were no real science fiction fans until the 20th century, when the term science fiction was invented. Science fictional ideas slowly became popular in the 19th century periodical, gained momentum in the first half of the 20th century, and became very popular in the second half. Most of the 19th century stories were wild, fantastic and even silly. They are rarely read today, and seldom anthologized. For example, here is one to try, “Rappaccini’s Daughter” by Nathaniel Hawthorne, first published in 1844.

I’m encouraging modern SF fans to read modern SF short stories, then then to explore the history of SF stories, because they have a rich heritage and are a wonderful art form, if you can get into them. Most readers no longer like reading short stories. When I was growing up back in the 1960s, reading the science fiction digest magazines was my introduction to science fiction fandom, but also to a mother lode of science fictional ideas. SF novels are usually plot driven, whereas SF short stories are idea driven. Science fiction short stories are memorable for wild, far out ideas, thinking out of the box, pushing the limits of new concepts, experimenting with writing techniques, exploring borders between the known and the unknown, and just having a lot of fun by endless speculation about possible futures.

Like I said, few science fiction fans read the current print and online magazines that publish science fiction, and far fewer still go back and read the older stories where science fiction began. Older stories reflect an evolution of thinking in general, and specific writing styles over time. To be honest, most past science fiction stories aren’t worth reading, even many that were collected into anthologies. Editors constantly resurvey the genre publishing retrospective anthologies looking at our genre history with new eyes, and often old favorites disappear over time. Few science fiction short stories are worth reading when they are published, and far fewer older stories are worth remembering by modern minds. But some are, and over the years and decades, anthologists have collected them.

From the first issue of Amazing Stories till the present, magazines and original anthologies have generated millions of science fictional ideas. Sure the science fiction novel and movie are the far more famous, but it’s the short story that’s the evolutionary engine of the genre. With less at stake, writers can easily experiment in the shorter forms of fiction, and the short story seems to bring out more variety of science fictional ideas. Sadly, the art of short fiction is disappearing from the genre just as fast as it has disappeared from the fictional mainstream. Few science fiction fans read SF short fiction, either in the dying print format, or the emerging online electronic formats.

At the Classic Science Fiction book club we try to remedy this by discussing one short story a week. Few members join in, but there’s enough to keep the feature going. For the first couple of years we only picked stories that were free on the net to make it easy for members to find and read. As it’s gotten harder to find free reprints of classic stories, we’ve decided to pick a big anthology of stories that can be our textbook. The book we want has to have a great selection, be readily available used, and cheap. Two were nominated, The Science Fiction Hall of Fame: The Greatest Science Fiction Stories Ever and The Ascent of Wonder edited by David Hartwell, with the Hall of Fame volume winning out. It’s pretty easy to find both of these books for less than $5 at ABE Books and Amazon.

This got me to thinking: “What were the greatest SF retrospective anthologies ever?” It seems like every decade of my reading life some editor has come out with a huge anthology that surveys all of science fiction for its absolute best stories. New SF readers need an introduction to the history of the short works of science fiction, but that introduction always needs to be updated.

When I was growing up reading science fiction short stories in the digest magazines F&SF, Galaxy, If, Analog, Amazing and Fantastic, short SF was considered the heart of science fiction because of the high concentration of exciting science fictional ideas. Old timers would talk about the great stories from the pulp era, usually describing the idea and not the plot, and there were many anthologies that collected these stories for new SF fans to catch up on the past. Hell, most of the great SF novels we baby boomers read first appeared as a series of short stories, and they were called fix-up novels, like City, The Foundation Trilogy, A Canticle for Leibowitz, More than Human, A Case of Conscience, etc., or they were famous collections like I, Robot, The Martian Chronicles, The Illustrated Man, The Menace from Earth, etc.

Fans of the genre usually attribute the beginning of science fiction to the publication of Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories (April, 1926) but short fiction featuring science fictional ideas have been around a very long time. At first Gernsback called his stories scientifiction, trying to classify a certain kind of story. Before that, sometimes this unknown type of story was called the scientific romance. Sam Moskowitz create a number of anthologies featuring earlier science fiction such as Masterpieces of Science Fiction (1650-1935), Science Fiction in Old San Francisco (1854-1890), Science Fiction by Gaslight (1891-1911) and Under the Moons of Mars (1912-1920). More can be read about these pre-Amazing era of science fiction in Pilgrims Through Space and Time by J. O. Bailey, a classic study first published in 1947.

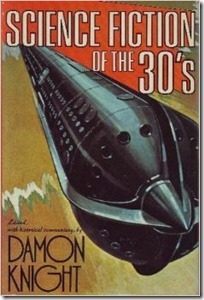

During the late 1920s and for most of the 1930s, Amazing Stories, Thrilling Wonder and Astounding Science Fiction was the primary source of science fiction as it wasn’t common yet to publish such genre stories in book form. This era is decidedly different than what came afterwards, what the first fandom read and loved. There are two great anthologies to track down if you want to get a taste of 1930s science fiction, Before the Golden Age edited by Isaac Asimov, and Science Fiction of the 30’s edited by Damon Knight.

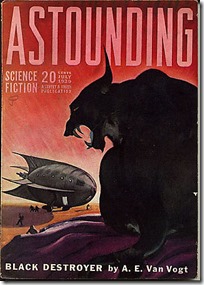

Then in July, 1939 John W. Campbell published his famous issue of Astounding Science Fiction, and what later old timers called The Golden Age of Science Fiction began. Much of what came out in hardcover from the legendary small press publishers, Gnome Press, Fantasy Press, Shasta, in the early 1950s, first appeared in the pulps in the 1940s. Few modern science fiction fans know about John W. Campbell and how he changed the direction of science fiction. He’s famous for discovering Robert A. Heinlein and Isaac Asimov, among many others.

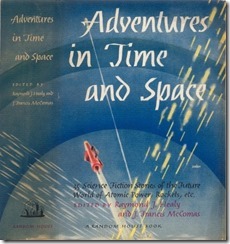

Then right after the war, in 1946, maybe because WWII involved atomic bombs and V-2 rockets, or maybe it was just time, two retrospective science fiction anthologies of science fiction short stories were published, Adventures in Time and Space edited by Raymond J. Healy and J. Francis McComas, and The Best of Science Fiction edited by Geoff Conklin. I discovered both anthologies as tattered library books in the early 1960s as a neophyte SF fan. The first, and the one that made the biggest impression on me was Adventures in Time and Space (Toc). It was a huge book that collected stories that defined that first The Golden Age of Science Fiction. Growing up talking to older fans I always thought the Golden Age of Science Fiction was 1939-1949, but later learn the golden age of science fiction was 12. Every year we have twelve-year-olds discovering science fiction books, but how many today ever discover the new short stories, much less the classic short stories?

In my early teens, the stories I read in the digest magazines Galaxy, If, Amazing, F&SF and Analog, would define my Golden Age nostalgia at 62. 1950s science fiction discovered in the early 1960s, along with newer writers like Samuel R. Delany, Roger Zelazny, J. G. Ballard, John Brunner, created my definition of science fiction, that is essentially unchanged today, and I assume is different from how younger generations define science fiction.

I also assume subsequent generations of SF fans will look back and define SF differently, and they probably don’t include SF short stories in their formative years. Their Golden Age of Science Fiction might be Star Trek, or Star Wars, or video games I don’t even know the name of. However, science fiction continued to produce short stories, and a few people read them and will remember them.

What anthologies are there for every Golden Age period of science fiction that have come out in the last 60+ years? The four pictured below cover the 1940s and 1950s, but sadly they are out of print. They can be found used if readers take the trouble, but probably 99.9% of science fiction readers don’t take the trouble. As newer retrospective anthologies come out, fewer stories from these years become representative, because more recent anthologies have to cover longer stretches of classic science fiction short stories. In the early 1960s I had to discover these 1940s books.

I eventually bought Adventures in Time and Space, but not the original 1946 edition, the 1957 Modern Library reprint. I lost that copy over the years, and now have 1990 SFBC edition. I reread this famous anthology every ten or fifteen years to take me back to the headspace of my childhood. Every time I reread “Requiem,” “Forgetfulness,” “Black Destroyer,” “Nightfall,” “Farewell to the Master,” “By His Bootstraps,” and many others, I’m reacquainted with 1940s science fiction, and the 1964 me. These stories were already over two decades old when I first read them, and they had a feel of quaintness fifty years ago, so I wonder what teens today will think of them?

Even though I’m encouraging younger readers to try these old stories, I have to warn you, they are old. Not as ancient as those from the 19th century, but they represent a different mindset than what I assume a kid today has. Part of reading anything old, whether it’s The Bible, Dante, Shakespeare, or Mark Twain, is you’re exploring ancient thoughts and thinking. Some old writers can actually speak across time and still have vitality. Most writers can’t. You read those writers with an academic mind, playing both an English professor, anthropologist, and historian.

Science fiction is often described as evoking a sense of wonder. Reading these old stories is like being the Indiana Jones of science fiction, looking for rare treasures of wonder, working as an archeologist uncovering ancient far out ideas and trying to piece together the evolution of science fictional memes.

Adventures in Time and Space is a rare example of a retrospective anthology getting reprinted, and although it’s been reprinted many times, it’s long out of print. For some reason many anthologies seldom get reprinted or stay in print. I guess it’s a copyright issue. So most of these books I mention here are not in print. Which is a shame, because they represent a special kind of history – our genre history. And wouldn’t it be great if someone could reprint all these wonderful books as ebooks and audiobooks?

The Best of Science Fiction (ToC) edited by Geoff Conklin, that also came out in that breakthrough year of 1946, never had the lasting fame as Adventures in Time and Space. This historical collection was reprinted once in 1980 as The Golden Age of Science Fiction. Geoff Conklin went on to edit many more science fiction anthologies, but none of them became classic like Adventures in Time and Space. If you can get ahold of a copy of the Healy and McComas volume it contains some of the most remembered stories from the late 1930s and early 1940s era. Wikipedia shows its table of contents and many of the stories and authors have links to entries. Of course, the titles in red are the stories now forgotten. By modern standards, these tales are still part of the ancient history of science fiction.

Starting in 1949, and running through 1958, T. E. Dikty and Everett F. Bleiler started an annual anthology series that collected the best stories of the previous year. Then from 1956-1968 Judith Merrill created her The Year’s Best S-F series.

All through the 1950s there were periodic collections for F&SF and Galaxy magazines that collected the best stories.

In 1959, Anthony Boucher edited A Treasury of Great Science Fiction, a two volume anthology that collected 4 short novels, 12 novelettes and 8 short stories to give a really big overview of the science fiction genre. For years this two volume set was a prime inducement to join the Science Fiction Book Club (SFBC), and gave new fans a sense of SF history. It’s not really a great collection for a retrospective short stories because it was dominated by four novels, although great ones. See TocV1, TocV2, because it might be worth collecting. Volume 2 has Brain Wave by Poul Anderson and The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester, a couple of my favorites.

Starting in 1965 and running till 1990, Donald Wollheim edited World’s Best SF. Wollheim was the Gardner Dozois of his day, or maybe I should say Dozois is the Wollheim of today. These were my favorites annual reads when growing up, and couldn’t resist showing four covers that are burned into my memory. Wollheim’s taste was closer to mine than Judith Merril.

At the beginning of 1970s, one of the greatest retrospective SF anthologies ever came out, The Science Fiction Hall of Fame (ToC), edited by Robert Silverberg. The selection is so great that every story has an entry at Wikipedia. That says a lot if a story is remember well enough for people to write a history about it for an encyclopedia. This book is still in print, and has often been reprinted. It is one of the most famous science fiction anthologies ever, but it only collects stories published through 1963, and time rolls forward. Ben Bova, Terry Carr and Arthur C. Clarke edited four more volumes in the series: Two A, Two B, Three and Four. Annoyingly, only v. 1 and 2a and 2b are in print, but they do collect some of the most famous and loved short stories of science fiction.

In the later 1970s I started seeing some odd mass market paperbacks called The Road to Science Fiction, edited by James Gunn. Eventually they included six volumes:

- The Road to Science Fiction: From Gilgamesh to Wells (1977) (ToC)

- The Road to Science Fiction 2: From Wells to Heinlein (1979) (ToC)

- The Road to Science Fiction 3: From Heinlein to Here (1979) (ToC)

- The Road to Science Fiction 4: From Here to Forever (1982) (ToC)

- The Road to Science Fiction 5: The British Way (1998) (ToC)

- The Road to Science Fiction 6: Around the World (1998) (ToC)

The original four came out as mass market paperbacks, but eventually reprinted as trade editions when the last two volumes completed the series. They can be expensive to track down now, which is rather depressing, since they make a very nice overview of science fiction. Even the Kindle edition of volume one is $31.49, and the trade paper of volume 3 is $57.75, which means few people will ever buy them.

Since 1953, The Hugo Award, selected by fans, has been given to short stories and novelettes, and in 1968 they created the novella category. If you follow the links from the story length you’ll see listings of famous stories published since then. Since 1966, The Nebula Award, selected by writers, have been given for short stories, novelettes, and novellas. Again, follow the links to the listings. Over the years these award winning stories have been collected into anthologies for The Hugo Winners (5 volumes) and The Nebula Awards (1-33, 2000-).

In 1992, Tom Shippey edited The Oxford Book of Science Fiction Stories (ToC) which aimed to give a concise collection of 20th century science fiction. Luckily this volume is still in print.

Then in 1993, Ursula K. Le Guin and Brian Attebery took another look at 1960-1990 American science fiction short stories with their book, The Norton Book of Science Fiction (ToC). Not quite a SF feminist manifesto, this anthology included far more women writers than prior retrospective collections.

In 1994, David Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer came out with one of the biggest retrospective anthologies ever, The Ascent of Wonder: The Evolution of Hard SF (ToC), with stories going back to 1844 (“Rappaccini’s Daughter” by Nathaniel Hawthorne). This massive book, almost a 1,000 pages, took a new look at the complete history of the science fiction short story, with the focus on real science fiction. Sadly, this one is out of print.

The 1990s was a great decade for retrospective anthologies, especial this two volume set edited by Pamela Sargent that showed a different look at science fiction, emphasizing how women wrote SF. Women of Wonder: The Classic Years (1940s-1970s) (Toc) and Women of Wonder: The Contemporary Years (1970s-1990s) (ToC).

Since 1984 Gardner Dozois has been editing the annual The Year’s Best Science Fiction. If you don’t currently read the printed or online SF magazines, this is one of two great annual resources to keep up with short science fiction. The other is David Hartwell’s Year’s Best SF which started in 1996.

Internet Science Fiction Database offers lists of top stories and anthologies at their site on their ISFDB Top 100 Lists. Sci-Fi Lists, a fan polling site offers Top 100 Sci-Fi Sort Fiction, and Next 100 SF Short Fiction. Ian Sales offers “The list: 100 Great Science Fiction Stories by Women.” Free Speculative Fiction Online links to legal free copies of science fiction short stories.

Any story that catches you attention from the table of contents listed here can be researched at ISFDB to see if it’s in an anthology you already own.

Current Print and Online Science Fiction Magazines

- Analog Science Fiction and Fact

- Asimov’s Science Fiction

- Clarkesworld

- Daily Science Fiction

- Fantasy & Science Fiction

- Interzone

- Lightspeed

- Strange Horizons

- Tor.com

History of the Short Story

- Great overview at Wikipedia

- A Short History of the Short Story by William Boyd

- A Brief Survey of the Short Story – series at The Guardian

- The American Short Story: A Selective Chronology

JWH – 1/23/14 – Table of Contents

What a great post! thanks so much for the useful overview of the SF story.

“Let’s face it, the short story is a fading art form that most modern readers ignore.”

I question your supposition. E-readers and tablets have made short stories more popular now than ever. I’ve read several articles making that case and from good sources, Publisher’s Weekly, etc.

That’s great to hear David! Let’s hope short stories make a comeback. You’d think reading short stories for our short attention generation would be perfect, especially read on a smartphone. However, I’ve been surveying short stories for the Kindle and Audible.com, and even though there’s plenty of public domain offerings, it tends to be the same old stuff. What’s needed are great anthologies, like The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Adventures in Space and Time, and The Ascent of Wonder.

I also think the short story is alive and well, especially in the world of science fiction and fantasy. It’s a subculture, so it’s smaller than, say, the community of novel readers, but it’s very much alive and thriving (and that’s a great thing!).

Thanks for the article, James! A great read!

Science fiction and fan fiction seem to be two areas where the short story has a good crowd fans, but I doubt it’s more than 50,000-100,000 people out of 7 billion. Movies and television just flat out dominate as an art form. If you read Entertainment Weekly pay attention how often they mention short stories. I think it’s about as often as they mention opera, but at least that’s more than they mention poetry.

Asimov’s SF and Analog used to have over a hundred thousand subscribers, but now it’s in the 20,000-30,000 range. It would be interesting to know how many people buy Dozois and Hartwell’s annual anthologies. I’m hoping more people will discover the short story. I’m a big fan. I think it helps that both of those anthologies are available as ebooks, and it would be a further help if they had audiobook editions.

What a wonderful, wonderful, wonderful post!

Yes, Jim, there are a few of us – a very, very few, and perhaps a dying breed, but we do exist: book fans who not only love science fiction, but whose first love is short form science fiction.

And among those, there exist in this world a handful – I think I may well be the only one in my country – of fans whose primary fascination is with the classic, older material, particularly the iconic (or definitive, or canonical) anthologies.

After some years of battling to keep up with contemporary short SF, I have decided to scale down my reading of the new stuff and retreat to my comfort zone, the good old stuff (as Gardner Dozois had it in a book title).

For you see, I missed most of it. I was born a mere three years after you, but my exposure to short SF started more or less eight to ten years later, when I bought Towards Infinity and Beyond Tomorrow, edited by Damon Knight (and “Towards” is not a typo, by the way – that’s how the British Pan Books edition was titled), and not long afterwards, Star Science Fiction Stories, edited by Frederik Pohl, and one fine morning in 1974, the Sphere edition of the first Hall of Fame volume. I’m sure you’ll agree that those are pretty good choices to start with!

After that, life happened, and I read fairly little science fiction of any sort until just a few years ago. But in the last decade or so, I’ve accumulated around 200 anthologies and collections. I’ve made many lists and indexes of these, including a main story index that runs to over 5, 000 entries (with many duplications, of course – I have at least 8 texts of “Nightfall”, for example).

But I still feel that there’s a lot of classic material I haven’t read yet, so I’ve decided to start ordering milestone books in a more or less organised way.

And so, just yesterday, I took The Arbor House Treasury of Modern Science Fiction, edited by Robert Silverberg and Martin H. Greenberg, out of its mailing box. Im sure you, and a few others who follow your posts, can understand the pleasure of this, only too well…

Thanks Peter for testifying about the greatness of SF anthologies. Maybe younger readers will take note. You should join our Classics of Science Fiction group, see the link in the post. Many of us love the old stuff from the 1950s and 1960s. We read the new stuff, but it’s the good old stuff that thrills us the most.

You should write a blog about your collection and indexing efforts – or have you? Have your indexing revealed which stories were anthologized the most?

You might be of the right vintage to point me in the direction to find a short story I read in early ‘60s. I remember it to be about a conversation between a few (couple?) individuals, in a cafe or bar, about the ever-growing and uniquitous telephone/telegraph network, and how the number of connections around the globe was beginning to bear some similarity to neural connections in the brain. Someone posed the question about whether this could form an intelligence, which might manifest itself as something of a threat, then all the phones, everywhere, stated ringing at once. Recognize this? Any memories or suggestions where to look? Anyone?

That doesn’t ring my phone, but if you ever find out, let me know, I’d like to read it. For a story from the 1960s that would be very insightful. I’ll post your query to the SF group I’m in on Facebook.

If you do Facebook, you might want to join this group https://www.facebook.com/groups/sciencefictionbookclub/

They believe your story is “Dial F for Frankenstein” by Arthur C. Clarke.

They also pointed out there’s a website for finding forgotten stories http://tasat.ucsd.edu/ – which I didn’t know about.

I read the new stuff, too – but I’m frequently frustrated by it. I have a blog, but there’s nothing on it – laziness and having to work for a living are a killer combo in this regard. You’re most welcome to a copy of my master spreadsheet of stories (Excel 2013). If interested, just give me an e-mail address to send it to. By the way, I did a quick check and found ELEVEN copies of “Nightfall”! One of these isn’t on the spreadsheet – it’s on my Asimov’s Index, which is a different spreadsheet (The story was reprinted in Asimov’s Science Fiction in 2007). “Nightfall” is clearly the champion, in my house, at least. I found six copies of “A Meeting with Medusa”, which appears to be second (although I didn’t go all the way through the alphabet).

I looked again – “Sailing to Byzantium” must surely be second, with 9 copies. This includes author collections and the original printing in the magazine. If author collections don’t count, you have a different picture, of course.

For my purposes I wouldn’t count the author collections. Not that ain’t important.

Check on “The Cold Equations” by Tom Godwin, it seems to be very anthologized. Here’s the list at ISFDB.

http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/title.cgi?55860

There’s no reason for long stories not to be idea-driven, be it SF or any other genre.

That’s true. But if you read 300 pages of short stories and 300 pages of a novel, you’ll get way more variety of ideas from the short stories. I tend to prefer novels, but I’m always surprised when I go on a short story reading jag by how wildly inventive writers can be.

David Lindsay’s SF Novel “A Voyage To Arcturus” follows a whole wreath of ideas.

My friend is looking for a short story he said he read it about 40 years back, the title which he thought was “Skirmish” (not the Clifford Simak one). He suspects it was a 1940’s era story and was part of an anthology of short stories. He thinks it was a UK story but could be wrong.

It starts with a series of mishaps and the main character treads on something and wonders how it knew he would tread in that spot and then has a series of mishaps with machines and objects until he decides that It is in fact a war…. he can remember the story but neglected to read the author. Basically all inanimate objects conspire against us making things break down, dropping vital bits that roll into inaccessible places.

Anyone have any ideas?

Have you tried ISFDB.org? It lists several short stories entitled “Skirmish.”

http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/se.cgi?arg=Skirmish&type=Fiction+Titles

I can’t argue with you about the short story as integral to the development of modern science fiction,but while it was evolving as a form in the old pulp magazines,a non-generic SF was also being published alongside it.With the emergence of SF as a paperback book category however,the gulf that had existed between the SF published in pulp magazines and general literature began to narrow and increasingly merged closer together.

It’s not surprsing therefore that there was a diminishing interest in short stories,even though they were a fertile breeding ground for rising authors who would later be attracted to the paperback realm.This is just an admission of fact,not a criticism of the short story form.

Love this blog. It keeps me so busy looking as I have a gazillion titles to find and new stories to discover. There’s something special about the vintage stories. I also like the modern online ones too – it’s good to keep up with what’s new. Perihelion is one that you could add to your list.

I am definitely finding myself more and more drawn to the old anthologies!

Thanks James

Thanks, Poly. If you like old stories, you might like to join us at https://groups.io/g/The-Great-SF-Stories-1939-1963 – where we’re trying to gather fans of old science fiction short stories.

I’m glad you commented today. I was just working on an essay trying to convince young people to try reading the old stories, but I was getting discouraged. I’m just not sure if very many people at all love the old stories.

It depends what you mean by old.In the 1950s,the 30s and 40s were already old when compared to the changes that modern authors were bringing to the genre then.In the early 1960s,with the advances that were already happening with the emergence of the “new wave” and some individual authors,much of the 50s SF,was already old.The SF I alluded to in these last two decades though,has become lasting,as have the authors.This is the difference I think,between what is old and what is not old SF.

When I started reading SF short stories in the 1960s I got them from anthologies published in the 1950s, which collected stories mostly from the 1930s and 1940s. 1930s stories seemed primitive. 1940s stories felt a bit old. 1950s stories felt contemporary, 1960s stories felt Avant-garde. Now, in the 2010s, stories from the 1980s sometimes feel old. And I’ve started enjoying short stories from the 1900s.

Yeah, old is relative Richard. What I’m trying to get at though is young people often dismiss “old” stories because they feel quaint and strange, maybe offensive, sexist, racist, and politically incorrect. So they don’t try to read any. I’m hoping we can still find good old stories that have last appealing and will be acceptable by younger readers.

Yes,well,they have become classics.As it gets pass the 1970s,they become fewer,which is why they seem old.

Surprised that they are not more popular now then ever with the fast lane of life we are in now. I think that’s the appeal of online short-fiction, as you can read a story in one sitting. The older stories have an added nostalgia now too. I think they just need more of a platform.

I’m looking for a short story or at the very least, the title and author.

Unfortunately, the only thing that I can remember about the story is that the main character is a woman? maybe an alien called Vee.

I read it a long time ago as a child and every so often it just pops back in my head.

I struggle to recall such stories that made lasting impressions too. And so do others who love queries here. But this time, I don’t think you’ve given us enough to work with. Sorry. It might help to remember the anthology you read it in.